Posts Tagged manfred nowak

Creating a world without torture: March in review

Posted by World Without Torture in News & Clippings, Rehabilitation on 31/03/2014

We summarise some of the biggest news stories, statements, events and news from the World Without Torture blog, Facebook and Twitter pages over the month of March.

Don’t forget to keep checking the blog in the coming weeks for more. And click here to visit our Facebook page, and here to visit our Twitter feed.

‘Europe Act Now’ campaign changes the way Europe views Syrian refugees

For one week in March, we donated our Twitter feed to husband and wife Osama and Zaina, two Syrian refugees who fled Aleppo, Syria, to seek safety in Europe.

However, due to tough restrictions on movement and incredible bad luck, they now find themselves stuck in Greece with no possessions, following a robbery they experienced shortly after arriving in the country.

Their story is just one of many promoted by European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE) who are running the ‘Europe Act Now’ Twitter campaign to pressure politicians in Europe to alter the way Syrian refugees are viewed, with the ultimate aim to make their passages to safety in Europe easier.

To read about our role in the campaign just click this link.

New video, starring IRCT patron, explains the rights of torture survivors

The most popular story on our blog this month has been the release of a new video from the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR).

The video, which features Dr. Mechthild Wenk-Ansohn from BZFO, an IRCT member, and IRCT patron and former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture Manfred Nowak, discusses what rights torture survivors have under the United Nations Convention.

To view the video, just click this link.

On the Forefront: Restoring justice in Bangladesh

Each year almost 220,000 citizens in Bangladesh are tortured, mainly by the police.

That’s an incredibly high figure, and one which the Bangladesh Centre for Human Rights and Development (BCHRD) want to lower and, ultimately, eradicate.

The problem lies in the implementation of the UN Convention Against Torture, which Bangladesh became a signatory of in 1998. Despite this commitment, torture is still not punishable as a crime under domestic law, meaning perpetrators simply get away with their crimes.

To read more about what BCHRD are doing to restore justice, faith in the authorities, and equal rights, just click this link.

Egypt crackdown brings most arrests in decades (Washington Post)

One story we shared on Facebook this month received a lot of attention, which was particularly pleasing for IRCT member El Nadeem, Cairo, who were quoted in the piece.

The in-depth study from the Washington Post not only assesses the number of Egyptians in detention in recent months, but also looks at their treatment, their rights, and some of the stories of torture heard in recent months.

Click the link or the picture below to read the full story.

On the Forefront: Tackling torture in Cambodia

In June 2013, the Asian Human Rights Commission declared that torture in Cambodia is “systematic” with 141 documented cases of torture in police custody since 2010. With a population of nearly 15 million, perhaps the 141 figure seems low. However this figure is only officially documented cases – unreported instances of torture could be much higher.

And regardless of the numbers, Cambodia is a country still reeling from the terrible effects of the Khmer Rouge regime which, almost exactly 40 years ago, killed at least two-million people through the Cambodian Genocide.

The Transcultural Psychosocial Organisation Cambodia (TPO Cambodia) hope to end the negative effects from this horrifying regime and assist the people of Cambodia to escape trauma.

You can read more about their work by clicking this link.

#JusticeforVeli – Veli deserves compensation 14yrs after losing arm to Turkish authorities

Veli’s story is complex, unusual, and powerful. Caught up in a prison siege in Turkey in 2000, Veli lost his arms after armed security forces stormed his prison block with a bulldozer which tore down the wall where Veli was standing, ripping off his right arm.

Veli’s story is complex, unusual, and powerful. Caught up in a prison siege in Turkey in 2000, Veli lost his arms after armed security forces stormed his prison block with a bulldozer which tore down the wall where Veli was standing, ripping off his right arm.

After years of torture rehabilitation and legal assistance from IRCT member the Human Rights Foundation of Turkey, Veli was granted a ruling from the European Court of Human Rights which specified his entitlement to compensation.

And so the compensation was paid – until the Turkish authorities overruled the payment. Now they demand that Veli pays the compensation back, at a much higher rate than it was awarded to him.

We joined the Human Rights Foundation Turkey in pressuring the state to end this case and to stop this extended miscarriage of justice by tweeting with the hashtag #JusticeforVeli.

To read more on Veli’s case, and to see how we are helping fight for his rights, click this link.

CVT’s transformation from a small local idea to a global, influential movement

The final ‘On the Forefront’ blog of March focused on Center for Victims of Torture (CVT). Based in the US, this IRCT member has a global reach, assisting victims of torture in the Middle-East, Africa and Asia.

Yet CVT was not always this large and, in fact, grew from only a small conversation with the Governor of Minnesota.

Today CVT is one of the leading networks in torture rehabilitation, prevention, and justice. To read more about the team at CVT and the excellent work they carry out across the globe, simply click this link.

For further information from World Without Torture, do not forget to ‘like’ us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter. Click here to visit our Facebook page, and here to visit our Twitter feed.

Explained: The rights of torture survivors

Posted by World Without Torture in From our members, Justice, Rehabilitation on 13/03/2014

A new video from the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) uses compelling interviews with leading professionals in the anti-torture field not only to explain the rights of torture victims, but to highlight existing barriers to torture rehabilitation.

The video, which features Dr. Mechthild Wenk-Ansohn from BZFO, an IRCT member, and IRCT patron and former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture Manfred Nowak, discusses what rights torture survivors have under the United Nations Convention Against Torture.

“Torture is one of the most serious human rights violations,” says Manfred Nowak in the piece. “Because of this, torture survivors are in need of whatever support and rehabilitation is available to overcome their experience of torture.

“Yet most of the time, rehabilitation is provided by centres in urgent need of money. There needs to be force on to states to provide full rehabilitation.”

The ECCHR is a human rights group which focuses on providing human rights litigation to hold state and non-state actors accountable for the violations of the rights of the most vulnerable.

It is their hope that with video pieces, such as this, more people will understand just how prevalent torture is around the world and what ore needs to be done to stop it.

You can watch the video below.

10 questions (and answers) about torture rehabilitation

Posted by World Without Torture in Advocacy and Influencing Policy, Governance, Justice, News & Clippings, Prevention, Rehabilitation on 14/02/2014

Many questions come to mind when thinking about torture. What methods are used? Where does it happen? Who does it? Who are the victims? We have answered many of those questions in this blog.

But how do victims overcome the trauma from torture? Or the physical sequelae left by brutal methods of torture? There are probably as many questions and doubts surrounding rehabilitation as there are about torture itself. Here are some of the answers.

1. What is rehabilitation?

Rehabilitation is simply ridding of the effects of torture – it is to empower the torture victim to resume as full a life as possible. Torture rehabilitation can take a variety of forms. In approaching it through a holistic approach, rehabilitation can include medical treatment for physical or psychological ailments resulting from torture; psychosocial counselling or trauma therapy; legal aid to pursue justice for the crimes; or programmes and activities to encourage economic viability, among others.

2. Why do torture victims need special treatment?

In many contexts, torture survivors seeking rehabilitation can only receive regular care and many physicians will not realise they are in the presence of a torture survivor. The risks associated with that are many and much has been written about that particular issue. In brief, not all therapeutic approaches have been described as useful in the treatment of victims of torture. Also, therapeutic procedures can easily recreate the torture experience, putting the torture survivors at risk of re-traumatisation.

The questioning, the testing instruments used, the physical space, the power relationship between the clinician and patient, etc., all have the potential to recreate the torture conditions, thus undermining the positive benefits of therapy. In some of situations, the treatment administered by non-specialized clinicians can even lead to harmful effects to the survivor.

3. What is the right to rehabilitation and is it an enshrined right by law?

In the first instance, the UN Convention Against Torture and other Cruel or Inhuman, Degrading Treatment or Punishment outlines the rights of an individual, outlaws torture, and promotes respect for the human rights of an individual.

Article 14 defines precisely that rehabilitation of a victim is a state responsibility which should be enforced in every complaint of torture. It reads:

“Each State Party shall ensure in its legal system that the victim of an act of torture obtains redress and has an enforceable right to fair and adequate compensation including the means for as full rehabilitation as possible.”

However, while there is a right to rehabilitation defined on paper by the UN, the right is not necessarily granted – even among the 154 state signatories. Also some countries have not ratified the convention into their national legal systems, and other countries have not signed the convention altogether.

4. What are some of the main forms of rehabilitation?

Rehabilitation programmes vary depending on the context in which the support is implemented, the resources available to the organisation issuing the programmes, and the nature of rehabilitation needed by the torture survivor. However some main forms of psychological and physiological support include: counselling; therapy, individually or group; psychotherapy; social reintegration programmes; medical assistance; artistic classes; exercise programmes; yoga; and much more.

5. Do the rehabilitation programmes work?

Yes. Targeted, tailored programmes of rehabilitation do not only allow the torture survivor to overcome their ordeal, but it can also allow their family, friends, or community to rebuild.

You only have to look at some of the stories from survivors of torture to realise that rehabilitation is fundamental is ensuring a victim of torture can live their life as fully as possible. You can read some stories of survivors by clicking this link.

6. Is rehabilitation ensured across the globe?

No. Even among the 154 state parties (across 80 different countries) to the UN Convention Against Torture and other Cruel or Inhuman, Degrading Treatment or Punishment, rehabilitation is not assured – at least not by the state. Across the world, some statistics point to torture being practiced in around 90% of the countries. Many of these do not provide adequate services for redress and rehabilitation through the state, so the responsibility falls onto anti-torture organisations – such as the IRCT members – who must move survivors past their experiences of torture, often with limited resources and under the watch of authoritarian regimes.

7. What is the IRCT, and what is its role in torture rehabilitation?

The IRCT is the largest membership-based civil society organisation to work in the field of torture rehabilitation and prevention. It is their mission to ensure there is access to rehabilitation services and justice for victims, and to contribute to torture prevention. Currently, the IRCT consists of 144 members across 74 countries.

8. How many people have been treated by the IRCT?

With members spread across more than 70 countries and the risks associated with the safety of torture survivors, accurate data collection is a significant challenge for the IRCT. However, figures gathered in the past suggested that more than 100,000 torture victims have been helped by IRCT member organisations across the globe on a single year.

9. Who can rehabilitation benefit?

The physical and mental after-effects of torture are far reaching but so are the benefits of rehabilitation. The victims but also their families, friends and sometimes their entire communities. There may be different approaches necessary in the rehabilitation programmes, and there may be different obstacles to rehabilitation, but the benefits can be felt by any victim of torture. To be as inclusive as possible, members of the IRCT network therefore tailor their programmes to best suit the contexts in which they operate.

10. Through rehabilitation, prevention and justice, can there be a world without torture?

Yes. The world can be rid of torture just like it was rid of slavery. Undoubtedly, the journey is long and full of obstacles, but with the right mix of rehabilitation, justice and prevention, the vision of a world without torture can be realised.

Ten facts to know about torture

Posted by World Without Torture in Justice, Prevention, Rehabilitation on 11/10/2012

Meeting new people outside IRCT or outside the circles of human rights work, we’ve found people have a number of questions about what the IRCT does and, more simply, about the issue of torture around the world. “Is there still torture?” they ask, often astounded that there is. For many, the term ‘torture’ invokes ideas of medieval torture chambers and the rack or the Iron Maiden.

Ten of the most common questions we get are the following:

1. Is there still torture today?

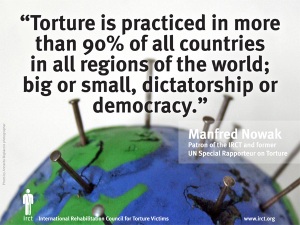

Sadly, yes, torture continues as a phenomenon today. In fact, torture takes place in the majority of countries in the world – as many as 90% of countries, estimates former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture Manfred Nowak. Furthermore, Nowak estimates that in as many as half of those countries, torture is a rampant and systematic problem.

2. Where does torture occur?

Torture most often takes place in places of detention – whether in the initial police lock-up, interrogation rooms, prison systems or other places where people are deprived of their liberty. This allows torture to remain a “secret” or “hidden” problem in the world [PDF]; places of detention are often well outside the realm of the public view and therefore escape public condemnation.

3. What exactly is torture?

The United Nations defines torture in the UN Convention Against Torture, and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment and Punishment as:

“… ‘torture’ means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.”

4. How are people tortured today?

While such techniques from the Middle Ages are no longer used on a large scale, the techniques of torture are still just as cruel, inhuman and painful to the victim. Furthermore, modern torture techniques are often designed to leave as few marks as possible to avoid possible future prosecution for the crimes. The Istanbul Protocol, the international guidelines for documenting torture, discusses torture methods under the following categories: beatings and other blunt traumas, beating of the feet (falanga), suspension, other positional tortures (such as being detained in a small cage or box, being forced to stand while arms are stretched high), electrical shocks, tooth torture, asphyxiation, rape and sexual torture. Other practices, such as hooding, humiliation, being stripped naked, threats to oneself or family, mock executions, simulated drowning (waterboarding) and sleep deprivation are also common torture methods that leave no external marks behind.

5. Why do people torture?

“The main aim of torture is to destroy the self-esteem of the person. The torturer tries to destroy the personal integrity by methods that cause maximum physical and mental pain and ensure gravest humiliation.”

While this is the main aim of torture, as described in Atlas of Torture, the goal of such pain and humiliation may vary. Police may torture a person to extract a confession for a crime or implicate others in a crime, as is a common practice in many countries, such as the Philippines; people may be tortured for information, as was the excuse used by the U.S. for the CIA torture programme in the so-called ‘war against terror’; armed forces may use rape and sexual torture to destroy the social fabric of communities. Or, state officials may employ torture as punishment for acts that person or a third person is believed to have committed.

6. Who commits torture?

For a case to be described as torture, the crime must be committed by a public official or a person acting in an official capacity, such as a state authority like police officers, soldiers, armed militia, among others. This also may include teachers, healthcare workers, paramilitary groups or prison guards.

7. Who are the victims of torture?

The victims of torture can be anyone – any person simply in the wrong place at the wrong time can become a victim of torture. However, there is no doubt that some groups are at particular risk of torture, for example, the poor. As the IRCT stated in The London Declaration on Poverty and Torture, poverty is one of the major factors that keep people particularly vulnerable to torture and other ill-treatment. “Most of the victims and survivors of torture belong to the poorest and most disadvantaged sectors of society,” Nowak said in the 2011 Global Reading for 26 June.

This is, generally speaking, because poverty makes people vulnerable to abuses and leaves them without the ways and means of defending their rights. Other factors can marginalise people, leaving them vulnerable to torture; this includes groups such as women, children, the elderly, religious, ethnic or sexual minorities and political opposition groups, among others.

8. What are the effects of torture?

There has been a growing body of scientific research on the physical, emotional, and mental effects of torture. The physical effects of torture depend greatly on the method of torture used. Certain types of torture are related to specific symptoms and signs. For example, for survivors of falanga, a type of torture where the soles of the feat are beaten, effects may include smashed and broken heels, later causing slow and painful walking for only limited distances.

The psychological consequences are frequently persistent and invalidating. The prevailing manifestations include anxiety, depression, irritability, emotional instability, cognitive memory and attention problems, personality changes, behavioural disturbances, neurovegetative symptoms such as lack of energy, insomnia, nightmares, sexual dysfunction, and “survivor’s guilt”.

In other words, torture represents an extreme life stressor and exposure to torture increases the risk of developing psychiatric symptoms and subsequent dysfunction, social problems, marginalisation and poverty. We know that not everyone exposed develops psychiatric manifestations but that a number of genetic factors, including vulnerability to stress, proneness to anxiety, developmental deficits, previous psychiatric history, incapacitating physical consequences, quality of social environment and individual coping efforts, all play important roles. Furthermore, the more prolonged, repeated, and unpredictable the experience of torture is, the more traumatic it is and more serious the psychiatric consequences are likely to be.

9. What is rehabilitation?

We believe that all torture survivors and their families have a right to rehabilitation. Rehabilitation is simply ameliorating the effects of torture – it is to empower the torture victim to resume as full a life as possible.

Torture rehabilitation can take a variety of forms. In approaching it through a holistic approach, rehabilitation can include medical treatment for physical ailments resulting from torture; psychosocial counselling or trauma therapy; legal aid to pursue justice for the crimes; or programmes and activities to encourage economic viability, among others.

10. What can I do to help?

There are many ways in which supporters can help. The first and most direct help is of course donations to the IRCT for our work.

Another way in which supporters can help is to simply share the stories of torture survivors or human rights defenders. International support from the World Without Torture community can create unending pressure on authorities to live up to their human rights obligations, such as stopping torture, ending harassment of human rights defenders, or bringing perpetrators to justice, among others. Your tweets, Facebook updates, letters to state leaders: these are all ways in which we can together create unceasing pressure on authorities to stop torture.

Torture in black and white: books on torture

Posted by World Without Torture in News & Clippings on 17/04/2012

Recently, on our organisation’s website, we wrote about a new book from former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Professor Manfred Nowak. The book, titled Torture: the banality of the unfathomable (in German: Folter: Die Alltäglichkeit des Unfassbaren) chronicles Professor Nowak’s experiences in documenting torture around the world, both during his professional career and during his mandate for the UN, where he traveled to almost 20 countries in all regions of the world.

However, Nowak’s book is only in his native German; but it started us thinking about other books – both fiction and non-fiction – that address torture and its impact on the victims and their families. Similarly to our previous list on the top films, we present here our top books on torture. If there are any we have left off or neglected, please remind us in the comments.

To start, it’s fitting to point to the current UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Professor Juan Mendez, and his recent book Taking A Stand: The Evolution of Human Rights. Mendez, who is himself a torture victim from the Argentine Dirty War, describes it as; “a way to illustrate and enable people to understand how far we’ve come to make the international human rights groups diverse in their composition”. The book provides a very moving and in-depth telling of his own experiences as a torture victim in Latin America in the late 70s, and how since, he has dedicated his life to furthering the cause of human rights.

To start, it’s fitting to point to the current UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Professor Juan Mendez, and his recent book Taking A Stand: The Evolution of Human Rights. Mendez, who is himself a torture victim from the Argentine Dirty War, describes it as; “a way to illustrate and enable people to understand how far we’ve come to make the international human rights groups diverse in their composition”. The book provides a very moving and in-depth telling of his own experiences as a torture victim in Latin America in the late 70s, and how since, he has dedicated his life to furthering the cause of human rights.

Many staff here at the IRCT recommended Jane Mayer’s The Dark Side: The Inside Story of How the War on Terror Turned Into a War on American Ideals. Mayer examines the legal justification and excuses for the use of ‘enhanced interrogation techniques’ AKA torture, on terrorism suspects by the CIA. As a long-time foreign correspondent, war reporter, and now at the New Yorker, Mayer’s journalistic background and method in writing creates a well-researched and gripping account.

Many staff here at the IRCT recommended Jane Mayer’s The Dark Side: The Inside Story of How the War on Terror Turned Into a War on American Ideals. Mayer examines the legal justification and excuses for the use of ‘enhanced interrogation techniques’ AKA torture, on terrorism suspects by the CIA. As a long-time foreign correspondent, war reporter, and now at the New Yorker, Mayer’s journalistic background and method in writing creates a well-researched and gripping account.

Professor Juan Mendez actually recommended this historically-derived drama in an interview when his own book was published. Set in Chile, Dorfman chronicles a country seeking justice and peace after the violent Pinochet regime. Set several years after the end of the Pinochet dictatorship, Death and the Maiden follows the perspective of a women who hears the voice of the man who raped and tortured her several years prior – a man who is now a guest in her kitchen. Beautifully written, Dorfman’s play points to the long-term impact of torture.

Professor Juan Mendez actually recommended this historically-derived drama in an interview when his own book was published. Set in Chile, Dorfman chronicles a country seeking justice and peace after the violent Pinochet regime. Set several years after the end of the Pinochet dictatorship, Death and the Maiden follows the perspective of a women who hears the voice of the man who raped and tortured her several years prior – a man who is now a guest in her kitchen. Beautifully written, Dorfman’s play points to the long-term impact of torture.

While this may come as a surprise for some, George Orwell’s classic novel about a totalitarian state depicts well one of the tools of repression, fear, and control that occurs in such regimes. Although better known for its creation of terms such as ‘Orwellian’, ‘Big Brother’ and ‘though police’, the final chapters focus on the torture and interrogation of protagonist Winston Smith. Smith seeks love and individuality in this dystopian novel, only to find it snuffed out by apparatuses of the state.

While this may come as a surprise for some, George Orwell’s classic novel about a totalitarian state depicts well one of the tools of repression, fear, and control that occurs in such regimes. Although better known for its creation of terms such as ‘Orwellian’, ‘Big Brother’ and ‘though police’, the final chapters focus on the torture and interrogation of protagonist Winston Smith. Smith seeks love and individuality in this dystopian novel, only to find it snuffed out by apparatuses of the state.

The third book in our list written by a current or former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, The Treatment of Prisoners Under International Law is a seminal work on torture, human rights, and international law by Sir Nigel Rodley. Places of detention, such as prisons, immigration detention centres, police lock-ups, or psychiatric centres, are the most common space in which one would find torture in any given country. As such, Rodley’s book and descriptive analysis is a fundamental read for those interested in how international human rights law came to be applied to a wider manner of human rights concerns, such as the inhumane or ill-treatment of detainees.

The third book in our list written by a current or former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, The Treatment of Prisoners Under International Law is a seminal work on torture, human rights, and international law by Sir Nigel Rodley. Places of detention, such as prisons, immigration detention centres, police lock-ups, or psychiatric centres, are the most common space in which one would find torture in any given country. As such, Rodley’s book and descriptive analysis is a fundamental read for those interested in how international human rights law came to be applied to a wider manner of human rights concerns, such as the inhumane or ill-treatment of detainees.

Horacio Verbitsky, author of Confessions of an Argentine Dirty Warrior, is among the most well-known investigative journalist and human rights advocate in his native Argentina. After the ‘Dirty War’, the decades of human rights violations, extra-judicial killings, enforced disappearances, and torture in Argentina, the former perpetrators of these crimes – largely the military branches under the regime – kept silent. Impunity prevailed. Verbitsky’s book is a first-hand account of the confessions of retired navy officer Adolfo Scilingo, the first man to break the military’s pact of silence and come forth with the crimes.

Horacio Verbitsky, author of Confessions of an Argentine Dirty Warrior, is among the most well-known investigative journalist and human rights advocate in his native Argentina. After the ‘Dirty War’, the decades of human rights violations, extra-judicial killings, enforced disappearances, and torture in Argentina, the former perpetrators of these crimes – largely the military branches under the regime – kept silent. Impunity prevailed. Verbitsky’s book is a first-hand account of the confessions of retired navy officer Adolfo Scilingo, the first man to break the military’s pact of silence and come forth with the crimes.

Torture: Does It Make Us Safer? Is It Ever OK?: A Human Rights Perspective is a series of essays and analysis from some of the top human rights thinkers, experts, and anti-torture activists in the world on a range of timely, current issues in human rights and the discourse around torture, particularly in the era of the so-called ‘war on terror’. For example, Minky Worden, Media Director of Human Rights Watch, conducts a survey of countries that torture. Eitan Felner, formerly of the Center for Economic and Social Rights and B’Tselem, writes on the Israeli experience. Twelve essays comprise the book.

Torture: Does It Make Us Safer? Is It Ever OK?: A Human Rights Perspective is a series of essays and analysis from some of the top human rights thinkers, experts, and anti-torture activists in the world on a range of timely, current issues in human rights and the discourse around torture, particularly in the era of the so-called ‘war on terror’. For example, Minky Worden, Media Director of Human Rights Watch, conducts a survey of countries that torture. Eitan Felner, formerly of the Center for Economic and Social Rights and B’Tselem, writes on the Israeli experience. Twelve essays comprise the book.

There were a lot of memos that comprise the almost bureaucratic and systematic manner in which the U.S. government most recently approved the use of torture in interrogation. Among the most famous of these memos was a series of notes from former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. After 18 pages of interrogation techniques that defied well-established law on torture, Rumsfeld approved, thus leading to such atrocities as Abu Ghraib in Iraq, Guantanamo Bay Prison and Bagram Air Force Base in Afghanistan.

There were a lot of memos that comprise the almost bureaucratic and systematic manner in which the U.S. government most recently approved the use of torture in interrogation. Among the most famous of these memos was a series of notes from former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. After 18 pages of interrogation techniques that defied well-established law on torture, Rumsfeld approved, thus leading to such atrocities as Abu Ghraib in Iraq, Guantanamo Bay Prison and Bagram Air Force Base in Afghanistan.

Are there any we have missed? Please let us know in the comments.

Friday News Clippings

Posted by World Without Torture in News & Clippings on 11/11/2011

We have mostly been focused on our own news this week, as we announced earlier today – our Declaration on Poverty and Torture we hope will change the way states and international bodies look at this problem. Also in the news this week:

Manfred Nowak, the former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and the IRCT Patron, was interviewed by the Pakistan Daily Times in a Q&A session. We suggest reading the whole interview, but here are some highlights:

So, I think, torture is practiced in more than 90% of all countries in all regions of the world; big or small, dictatorship or democracy. I would say that in more than half the countries of the world, torture is widespread, or even systematic. And that is a very, very negative and disturbing conclusion.

President Bush and his administration have paid the world a very, very negative service by undermining the absolute prohibition of torture. I spoke to very high level officials in other countries and they say that if America is torturing openly, why shouldn’t we?

It’s the same with death penalty, there are always people who argue that death penalty has a deterrent effect, no, it’s the opposite, and it has a brutalising effect.

Human Rights Watch chronicles widespread abuses and torture from the military and police officers in the drug war. Their conclusion?

…Found evidence that strongly suggests the participation of security forces in more than 170 cases of torture, 39 “disappearances,” and 24 extrajudicial killings since Calderón took office in December 2006.

The UN Committee against Torture hears reports from Sri Lanka (which was particularly damning), Germany, Bulgaria, and Madagascar

If people could only see

Posted by World Without Torture in Uncategorized, Voices on 04/10/2011

–Manfred Nowak, IRCT Patron and former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture

If people and politicians would only know what goes on inside prisons, they would feel very differently. If they only knew of the amount of torture hidden behind prison walls, it might stop.

Please share this to spread a message against torture.